We started the morning on the Common, talking about the occupation and Bostonians' reactions to the presence of the soldiers. Then, it was on to the Granary Burying Ground and Kings Chapel, where Prof. Lepore generously allowed me to say a few words about gravestones and memorialization. In King's Chapel, I had a chance to sit in Ame and Elizabeth Cuming's pew (#36), which was a real treat. They had a window seat just a few boxes back from Governor Hutchinson.

Next, we walked down to the Town House, where the students pondered the architectural embodiment of imperial authority. The poor little Town House looks so small next to all of the modern sky scrapers — it's a bit difficult to imagine it as an imposing, impressive, opulent building. Yet, the view down old King Street (now State Street) to the Long Wharf remains unobstructed. Prof. Lepore made sure to point out the orientation of the building, facing eastward, toward the wharf, the ocean, and London. If you can imagine a ray of power emanating from the King and connecting to the Council Room in a straight line, it would run right up King Street.

Inside, we went through the exhibits pretty quickly. My favorite object in the collection was a tiny, gold-tipped cane that was (supposedly) Preston Brooks' weapon when he beat Charles Sumner. If it is, I don't know how Boston's Old State House Museum got hold of it. Despite the dubious provenance, I enjoyed pondering this enigmatic little exhibit. I don't know if you can see it in this picture, but the cane is displayed in a glass case with three random pieces of fancy silverware. Why? If there was a reason, it was not apparent to me.

Inside, we went through the exhibits pretty quickly. My favorite object in the collection was a tiny, gold-tipped cane that was (supposedly) Preston Brooks' weapon when he beat Charles Sumner. If it is, I don't know how Boston's Old State House Museum got hold of it. Despite the dubious provenance, I enjoyed pondering this enigmatic little exhibit. I don't know if you can see it in this picture, but the cane is displayed in a glass case with three random pieces of fancy silverware. Why? If there was a reason, it was not apparent to me.From the Town House, we walked down old King Street, out onto the Long Wharf, and to the harbor. From the end of the wharf, we could look back and glimpse the cupola of the Town House nestled among the financial buildings.

Can you see it back there? It's the tiny little point just above that white van. It takes a lot of imagining to turn that puny building into an imposing structure towering over the shops and standing among the steeples. I thought that Prof. Lepore made a good point, though — the modern surroundings are actually helpful in trying to recapture royal officials' first impressions of Boston as provincial and pathetic. Just imagine that everything for half a mile around the New England Aquarium is a burned-out soot pit, still waiting to be rebuilt after the fire of 1760, and you have a good idea of what a Londoner might have seen as he stepped of onto American soil for the first time.

After this, we walked by Fanueil Hall and up into the North End. A quick tour of Copp's Hill Burying Ground, a peek into Old North Church, and a nod to Paul Revere's house completed the first leg of our journey.

We had lunch at Regina Pizzeria and then hopped on the T to the MFA. There is only one small room of Copley paintings, but there are some greats on display. We saw Boy With a Squirrel, Nicholas Boylston, Mercy Otis Warren, John Hancock, and Watson and the Shark. I had never seen the Henry Pelham portrait in person before and was surprised by the smears of white on the subject's cuffs and collar. From 10+ feet away, the thick white paint creates texture, but up close (with my new glasses), it looks very thick.

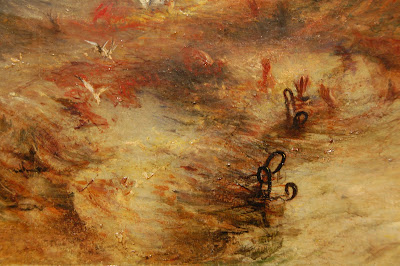

We dispersed after viewing this exhibit, but I stayed at the MFA for a while on my own. One painting in the European gallery caught my eye: Joseph Mallord William Turner's Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) (1840). It's so horrifically violent, but, at the same time, quite beautiful. It is partially based on accounts of the Zong Massacre. I think it would be easy to paint a shocking, gory depiction of slaves being tortured or killed, but this painting is so arresting because it looks almost like a delicate maritime sunset until you look again and it becomes gruesome. That sea of hands is primal. Had any of the cave paintings of hands been discovered in 1840? That's what I thought of when I saw this painting.

That's all for today — 18th-century Boston may have been a small city, but I feel like I've walked every inch of it and my feet are killing me.

1 comment:

At first, I thought that those people on YouTube were going to do the electric slide.

We used to sing "Coronation" at church services during Civil War reenactments. No synthesizers, though.

Post a Comment